Encoded within Shostakovich's Symphony No.10 is a message of individual defiance against tyranny.

The Russian composer Dmitri Shostakovich was twice denounced by Soviet authorities for writing music that was supposedly antithetical to the cultural values of the USSR (which itself proclaimed to be against the bourgeois, modernist and formalist music of the West, which it viewed as inaccessible to mass audiences). The first instance was in 1936 after Stalin's unfavourable reaction to the composer's opera Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk (despite the work's popularity up until that point), and the second came in 1948 after the disappointed reactions to his Eighth and Ninth Symphonies, with Central Committee secretary, Andrei Zhdano, accusing him of writing ‘inappropriate and formalist music’. Although he continued to compose, Shostakovich's music was banned from concert halls.

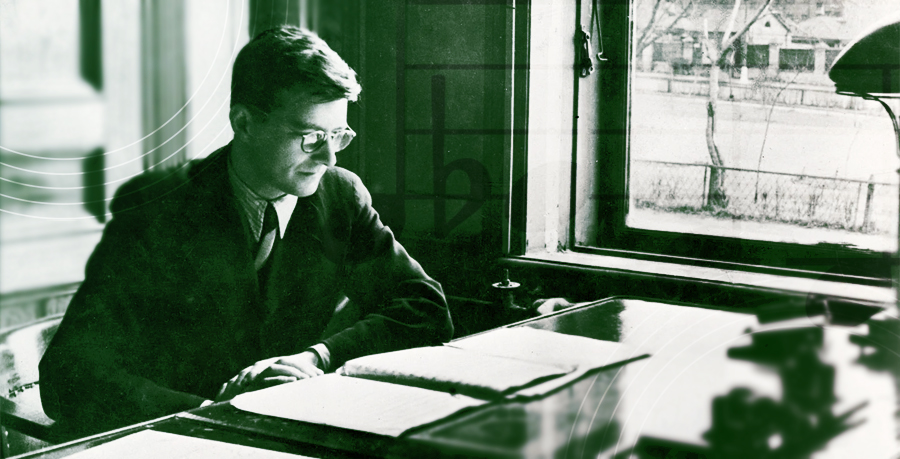

Conductor Yevgeny Mravinsky, Shostakovich and the Leningrad Philharmonic Orchestra after the premiere of the Tenth.

Conductor Yevgeny Mravinsky, Shostakovich and the Leningrad Philharmonic Orchestra after the premiere of the Tenth.

After Stalin's death in 1953, the premiere of his Tenth Symphony took place in Leningrad on 17 December that year. It is not exactly clear when the material of each movement was written, and it is likely that much of it was sketched out prior to 1953, but particularly notable in the fourth movement is a defiant four-note theme (heard at 11:59 in the track below) after the previous darkness and intensity that pervades the work.

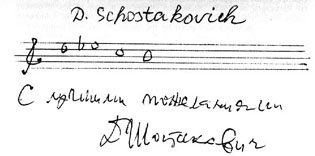

The basis of this theme is a musical cryptogram made from letters of Shostakovich's name in German (Dmitri Schostakowitsch), 'DSCH'. Understanding the translation of this signature to music requires some decoding.

The letters D and C can be found in standard music notation – so far, so good – but conventional notation, musical notes on the lines (or staff) only ranges form A to G. It is here that German musical notation becomes useful, the note of B natural is referred to with H (and uses 'B' to refer to B flat).

For the S, again, German nomenclature proved accommodating. The note E flat is to referred to as 'Es', a sibilance that allows Shostakovich to complete the music monogram with the notes D, E flat, C and B.

Shostakovich's musical and lettered signatures, courtesy of the DSCH Journal

The fourth movement isn't the only appearance of the motif. It actually appears earlier, in the waltz-like third movement Allegretto, juxtaposed and becoming increasingly intertwined with another name encoded in music: that of Elmira Nazirova, one of Shostakovich's pupils, who is represented by the notes E-A-E-D-A, or E-La-Mi-Re-A). Shostakovich and Nazirova maintained a life-long friendship.

Other composers have paid homage to Shostakovich with the use of the DSCH theme. Benjamin Britten, who became familiar with Shostakovich’s work upon hearing Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk in London in 1936, defended it against its critics saying that 'there is a consistency in style and method throughout. The satire is biting and brilliant.' It is perhaps in solidarity – though with some levity – he featured a transposed DSCH motif to the words 'silly fellow' in his 1943 cantata Rejoice in the Lamb.

Another of Shostakovich's pupils, Edison Denisov, featured the theme throughout his 1970 Sonata for Alto Saxophone and Piano, and Scottish composer Ronald Stevenson wrote a nearly hour-and-a-half 'theme and variations' on the motif in his Passacaglia on DSCH for the piano.

Shostakovich may not have been the first to write his own signature in music (Bach predated him with his own musical tetragram some 200 years earlier), but his music demonstrated, with considerable profundity, that it needn't be and exercise in mere vanity – but an inspiring message from a stubborn, wry and unshakeable soul, who continued to write music in spite of profound fears.

Hear Shostakovich's Symphony No.10 in concert at Southbank Centre's Royal Festival Hall on Tuesday 3 February, conducted by our Music Director Vasily Petrenko.