Sunday 27 April 2025, 3pm – Southbank Centre's Royal Festival Hall

Presented as part of Multitudes

Sibelius Finlandia 8 mins

Weill Four Walt Whitman Songs 17 mins

Interval: 20 minutes

Shostakovich Symphony No.7, 'Leningrad' 79 mins

Vasily Petrenko Conductor

Roderick Williams OBE Baritone

Kirill Serebrennikov Art Director

Ilya Shagalov Video Artist

Royal Philharmonic Orchestra

Discover more about the artists here

This performance is funded in part by the Kurt Weill Foundation for Music, Inc., New York, NY

Symphony of Shadows was commissioned by the Southbank Centre and the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra.

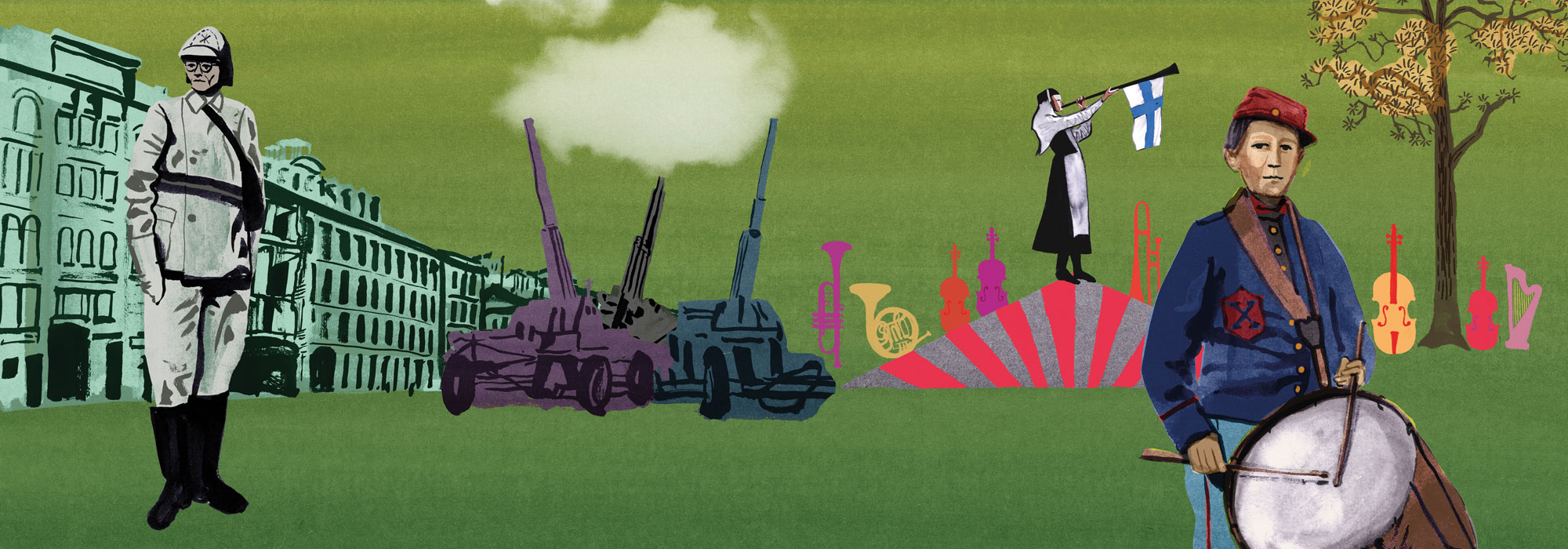

When the world falls apart, it is often music that survives and music that saves us. Today’s programme is a powerful tale of struggle and resistance in the face of unimaginable loss and the devastation of war, from a Finnish tone poem that helped to secure a nation’s independence, through a plaintive lament for the needlessly lost, to a work so devastating that it captured the attention of millions. Together, these works demonstrate the power that music has to shape worlds, to bind nations and even to influence peace.

This performance is part of Southbank Centre's Multitudes festival, where world-class orchestras join forces with some of the most ambitious and exciting artists, performers and creatives practising today. To visually interpret Shostakovich's powerful Seventh Symphony, a three-channel video installation by filmmaker Ilya Shagalov and art director Kirill Serebrennikov accompanies the orchestral performance, bringing Shostakovich’s music into the modern era through cutting-edge technology.

Finlandia (1899)

Jean Sibelius (1865–1957)

It is not too much of a stretch to say that independent Finland as we know it today is in part thanks to Jean Sibelius, and even to his tone poem Finlandia. From 1808 to 1917, Finland existed as a ‘Grand Duchy’ within the Russian empire, a ‘temporary’ occupation designed to put pressure on Sweden that ended up holding for more than a century. But as the 19th century wore on and Russian domination increased, so a wave of Finnish nationalism grew in response, and Sibelius found himself composing at its peak.

In 1899, Sibelius was asked to compose the music for a ‘Press Celebrations’ event at the Swedish Theatre in Helsinki. On the face of it, it was an event in aid of press workers’ pensions, but in fact, it was a protest against Russian press censorship and a fundraiser designed to support a new, free, Finnish press. Sibelius composed a series of seven tableaux for orchestra, each depicting an historic moment from Finland’s past – from the Thirty Years’ War to the Russian Invasion of 1714. But the last of the tableaux, ‘Finland Awakes’, spoke to hopes of a bright new future, its dark and ominous opening giving way to a jubilant brass fanfare that seems to herald the creation of a whole new world. And, while he did not explicitly base the work on original folk material, by mirroring modes common to Finnish folk music, Sibelius deftly manages to evoke the muted colours and vast landscapes of his homeland.

The work captivated the nation, and a year later, Sibelius arranged and published it as a standalone tone poem, Finlandia. Tracing a journey from darkness to light, from oppression to liberation, it became a symbol of hope and resistance for the Finnish people. When Finland finally gained independence in 1917, Finlandia became the people’s de facto national anthem, and Sibelius was proud to acknowledge the part that he – and his music – had played in the journey. ‘We fought 600 years for our freedom and I am part of the generation which achieved it. Freedom! My Finlandia is the story of this fight. It is the song of our battle, our hymn of victory.’

Did you know?

In order to defy the censors, Finlandia went by several more muted pseudonyms for many years, including ‘Happy feelings at the awakening of Finnish Spring’, ‘A Scandinavian Choral March’ and even the entirely non-descript ‘Impromptu’.

Four Walt Whitman Songs (1942–7)

Kurt Weill (1900–1950)

I. Beat! Beat! Drums!

II. Oh Captain! My Captain!

III. Come Up from the Fields, Father

IV. Dirge for Two Veterans

Little more than a decade after Finland freed itself from Russian occupation, across Europe emerged a very different kind of threat. After the ‘lean years’ that followed Adolf Hitler’s imprisonment in 1924, membership of the Nazi Party in Germany began to swell. By 1933, the Nazi Party had all but taken control of the political system, and the first concentration camps were established. Kurt Weill, then enjoying widespread success off the back of his The Threepenny Opera, quickly found himself the subject of deliberate targeting and persecution.

In 1933, Weill fled Germany for Paris, and two years later, moved to the United States, where he made New York his permanent home. He never looked back: ‘I have the feeling that most people who ever came to this country came for the same reasons which brought me here: fleeing from the hate, the oppression, the restlessness and troubles of the Old World to find freedom and happiness in a New World.’ In the years that followed, Weill embedded himself in American society and turned his attention to music for the theatre, leading to a string of successful Broadway shows. A decade after arriving, he became a naturalised American citizen, admitting that he had ‘never felt as much at home in my native land as I have from the first moment in the United States’.

So when, in 1941, Japanese troops launched a vicious, surprise attack on Pearl Harbor, killing more than 2,400 civilians and service personnel, Weill found himself moved to write a series of songs commemorating those lost. His set of three songs was joined five years later by a fourth, each of them composed to texts by the American poet Walt Whitman (1819–1892), written during the American Civil War. Together, the collection captures feelings of rage, disbelief, nostalgia and deep mourning, and is at once both an angry work of protest and a thoughtful, reflective response to the atrocities of war.

There is a kind of wry irony in Weill’s writing too, as he draws attention to the fact that the instruments used to call us to war are the very same instruments that will be used to console those left to mourn the dead. The opening song, Beat! Beat! Drums! is an adaptation of a military march, now transmuted into a funereal parade for the dead. Where the first song is full of rage, O Captain! My Captain! is more mournful, the sentiment one of heady nostalgia. Indeed, it is here that we get the strongest sense of Weill’s newly developed Broadway style, tugging on the heartstrings to devastating effect. The third song, Come Up from the Fields, Father (which was the last to be added to the set), is a tale of two halves. At first, it bristles with energy, the anticipation of receiving a letter from the battlefield keenly felt. But the excitement is short-lived, and the pace soon slows: ‘O this is not our son’s writing’. The letter brings news of their son’s death and we can only look on as yet another family’s future is irrevocably transformed by the deep weight of grief. The final song, Dirge for Two Veterans, takes us full circle and returns us to the drumbeat of the opening song. The two veterans here are father and son, killed in the same battle, and Weill’s eerie cabaret-esque setting – which is deeply melodic and at the same time dissonant and unsettling – forces us to confront why we often glorify such abject horrors.

Did you know?

Weill was married twice – both times to the singer and actress Lotte Lenya. They met in 1924, married in 1926, divorced in 1933 and married again in 1937.

Kurt Weill: Four Walt Whitman Songs – Surtitles by Ruth Hansford

Interval: 20 minutes

Symphony No.7 in C major, Op.60, 'Leningrad' (1941)

Dmitri Shostakovich (1906–1975)

I. Allegretto

II. Moderato (poco allegretto)

III. Adagio

IV. Allegro non troppo

On 22 June 1941, German forces invaded Russia’s capital, Leningrad. What followed would be one of the longest and most brutal sieges of the Second World War, lasting for almost two and a half years, killing more than a million of the city’s inhabitants, and reducing the city to rubble. Shostakovich was there to witness it first-hand. ‘On that peaceful summer morning’, he wrote, ‘I was on my way to the Leningrad Stadium to see my favourite Sunday soccer game… Molotov’s radio address found me hurrying down the street… Our fruitful, constructive existence was rudely shattered!’ But Shostakovich was not cowed. On the contrary, the intensity of the siege around him inspired a burst of creativity unlike anything he had experienced before. ‘Neither savage raids, German planes, nor the grim atmosphere of the beleaguered city could hinder the flow’, he later recalled. ‘I worked with an inhuman intensity I have never before reached.’

He completed the first three movements of what would become known as his ‘Leningrad’ Symphony that summer and, after an enforced hiatus during his family’s evacuation, completed the work in December. Shostakovich’s memoirs would later show that his ideas for the Seventh Symphony had taken root years earlier, and that the siege of 1941 had simply been a catalyst for a long-awaited unburdening. ‘It’s not about Leningrad under siege’, he explained, ‘it’s about the Leningrad that Stalin destroyed and that Hitler merely finished off.’ And yet, it is not a work of resignation and despair – it is one of extraordinary bravery and optimism. With its massive orchestra and barrage of percussion, the ‘Leningrad’ moves from invasion to victory, refusing to be cowed by totalitarianism.

Shostakovich was clear that the Symphony would not offer a literal depiction of the battlefield, rather he wanted to compose ‘music about terror’. So, the theme in the first movement that has been attributed variously as the ‘invasion’ theme, the ‘anti-Stalin’ theme or the ‘anti-Hitler’ theme is really all three of these. It is a symbol of oppression that gradually accrues magnitude and power, the threat at first distant and banal, but which becomes ever more distorted, sinister and grotesque. At nearly 30 minutes in duration, this gargantuan first movement dwarves the short scherzo that follows, itself superficially lyrical and yet eerily unsettling, so typical of Shostakovich. We know, really, that the melodic surface is but a mask but it is the central episode of the Adagio that confirms this – the battle march resurging remorselessly amidst a long, impassioned lament for the dead. Just like the opening movement, the finale begins with quiet understatement, the tension dormant and low-lying until it is almost too late. As Shostakovich allows the tension to ratchet little by little, we soon find ourselves confronting the opening ‘invasion’ theme once more – only now it is overpowered and overcome, the indomitable nature of the human spirit victorious in the face of fascism.

Leningrad itself would have to wait until August 1942 to hear the Symphony first hand. The premiere was given in Kuibyshev in March 1942 by the Orchestra of the Bolshoi Theatre, after which a microfilm of the score was smuggled out of Russia and delivered to Tehran, from where it was shipped to the US. This covert operation allowed Henry Wood to conduct a performance at the Proms in London on the anniversary of Russia’s invasion in June 1942, and for Toscanini to conduct a performance on America’s NBC radio in July that reached more than 20 million listeners. When it was finally performed in Leningrad a month later, loudspeakers were used to broadcast the work both to the city’s residents and to the German troops. Only 16 members of the original Leningrad Radio Orchestra had survived to take part, and eyewitness accounts speak of an orchestra of emaciated musicians, one of whom was said to have been rescued from the morgue where he had been mistakenly left for dead. That the performance was able to take place at all is an astonishing and moving tale of courage and resistance in the face of unimaginable terror.

Did you know?

The ‘Leningrad’ Symphony struck such a chord after its broadcast on NBC Radio that Shostakovich quickly became a symbol of global defiance, and his image even appeared on the cover of Time magazine in 1942.

Programme notes and listening recommendations by Jo Kirkbride, 2025

Fancy an encore?

After the concert, why not continue your own musical journey with a specially selected playlist of works inspired by today’s concert and further pieces from the Lights in the Dark series. Today, we recommend...

Weill’s Die sieben Todsünden (The Seven Deadly Sins), a ‘sung ballet’ composed to text by Bertolt Brecht when Weill arrived in Paris in 1933.

Sibelius’ Kullervo, his earliest ‘nationalist’ symphony for voices and orchestra, composed in 1892 and based upon poetry from Finland’s epic compilation Kalevala.

Shostakovich’s Symphony No.5, the work which Shostakovich would later say was closest to the ‘Leningrad’, depicting as it did his defiance in the face of Soviet oppression.

Discover our guide to the art for Lights in the Dark